What is Arctic history? Archival bias, scientific research, and the case of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik

By Dr Nanna Kaalund

When you think about Arctic history, what comes to mind? Typically, the word ‘Arctic’ evokes stories of exploration and scientific discovery. Sometimes it conjures images of nineteenth-century naval men bravely searching for a Northwest Passage. Other times it can present pictures of modern scientists dressed in high visibility orange snowsuits.

The Arctic, especially the high Arctic, has long held a special place in the imaginations of more southern based people. Often portrayed as a ‘terra nullius’, a frozen no-man’s land, early European cartographers wondered what was up there. What marvels might be revealed? This fascination with the Arctic, and the view of the Arctic as a space waiting to be uncovered and claimed, intensified in the nineteenth century.

Numerous large and small-scale expeditions tried to find a route to the Pacific or to reach the North Pole. They looked for minerals and other natural resources, and made elaborate scientific experiments. Following their ventures, many of these travellers published narratives that recounted their experiences and achievements. In doing so, the authors situated themselves within the long history of past explorers who had visited the Arctic. It was a construction of history which centered the trials and tribulations, as well as the triumphs, of European and Euro-American explorers.

When writing about Arctic history, especially the history of Arctic exploration, historians face a key problem: the emphasis on the accounts and experiences of the European and Euro-American explorers who visited the Arctic has resulted in a bias in the sources.

We know a lot about commanders and officers, and less about the other personnel participating in the expeditions, or about the whalers, missionaries, and traders working in the Arctic regions. The lives and experiences of Arctic Indigenous peoples, including Inuit and Métis, take up an even smaller portion of the annals of Arctic history.

In my recent article, “Erasure as a Tool of Nineteenth-Century European Exploration, and the Arctic Travels of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik” published in the Historical Journal, I show how the bias in Arctic history towards specific voices was a deliberate strategy used by explorers and expedition organisers to shape perceptions of their projects ‘at home’. By controlling who was seen as an Arctic explorer, and as an expert on Arctic matters, you could also direct master-narratives about Arctic exploration. This has had an enduring influence on both the historical presentation of the Arctic, and on modern Arctic geo-politics.

Tookoolito and Ipiirvik were a married couple from present-day Canada. As teenagers, they travelled with whalers to the United Kingdom. They were displayed in foreign living people shows and ethnological lectures, and even met the Queen. After they returned to the Arctic, Tookoolito and Ipiirvik worked with the whalers around Cumberland Sound. This was where they met the publisher-turned-explorer Charles Francis Hall. Though he had no experience with Arctic travel, Hall firmly believed that he could solve the mystery of John Franklin’s lost expedition by immersing himself in Inuit culture. As he wrote:

“Neither M’Clintock nor any other civilised person has yet been able to ascertain the facts. But, though no civilised persons knew the truth, it was clear to me that the Esquimaux (Eskimo) were aware of it, only it required peculiar tact and much time to induce them to make it known.”

This quotation shows how Hall made two important distinctions which are key for understanding the prevailing bias in Arctic history. Firstly, Hall contrasted ‘civilised persons’ with Inuit. Secondly, Hall differentiated between what Inuit knew and what ‘civilised persons’ could infer from it. In doing so, Hall both drew on and upheld structures of racialised othering of extra-Europeans, which allowed him to present himself as an Artic expert while erasing the expertise of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik.

It is difficult to overemphasise just how unqualified Hall was for Arctic travel when he first set foot on Buddington’s whaling ship. Both the whalers and Hall were aware that he needed help. Together with their extended families, Tookoolito and Ipiirvik had worked with the whalers before and after their voyage to the United Kingdom. They were known to be excellent guides and hunters, and they spoke English well. After being introduced to Hall by the whalers, they quickly became Hall’s most important allies for his Arctic projects. It was their knowledge and help that allowed Hall to transform himself into an Arctic expert.

Following his return from the Arctic, Hall was invited to speak at several scientific societies, and he embarked on a very popular lecture tour. In these public performances, Hall presented himself as uniquely knowledgeable about the Arctic, because he had adopted Inuit methods for travelling and living there, thereby enabling him to undertake research that had not been previously documented. Tookoolito and Ipiirvik were also part of the lectures, but they were not there to speak about their knowledge of the Arctic or their search efforts to find Franklin and his crew. By contrast, they were there to visually represent type-specimens of Inuit, and to provide entertainment for the audience and to bolster Hall’s credentials. Having Tookoolito, Ipiirvik, and their baby Tarralikitaq during his tour enabled Hall to further his claim and position himself as a gate-keeper of Inuit knowledge.

Hall was by no means the only person to establish his expertise by erasing the contributions and knowledge of others. It was a popular strategy throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in the Arctic and elsewhere. For the modern historian, this epistemic violence causes a very fundamental, practical problem: there are few archival sources that document the lives and experiences of the Indigenous peoples who worked as part of Arctic expeditions. Tookoolito and Ipiirvik are in many ways unique examples. They lived in the United States for many years, and there is archive that documents their lives.

However, their experience was not altogether that unique. Many European and Euro-American expeditions to the Arctic included Indigenous peoples, who, as was the case with Tookoolito and Ipiirvik, often performed labour that was essential to the success of the expeditions. Yet, their contributions were typically downplayed in the official accounts of their time in the Arctic. What is more, they were frequently described in the othering language of ethnographic observations, rather than as collaborators and co-travellers.

Just as Hall bolstered his credentials by presenting Tookoolito and Ipiirvik as ethnographic specimens rather than as co-travellers, so did other explorers also deliberately describe their knowledge-production in way that erased or minimised the contributions of Arctic Indigenous peoples. There is, therefore, a bias in historical sources that replicates itself to this day; it is difficult to recover information that was never meant to exist. Yet, it is not impossible. As the case of Tookoolito, Ipiirvik, and Hall shows, unpacking how the processes of nineteenth-century scientific knowledge making were entrenched in imperialistic structures of epistemic and physical exploitation, allows us to unravel how these structures have continued to be reproduced in Arctic studies today. It also highlights the role of the colonial archives and museums in upholding such narratives, and the potential for change in the future.

For more on the lives of Tookoolito and Ipiirvik, see: Sheila Nickerson (2002), Midnight to the North: The Untold Story of the Woman who Saved the Polaris Expedition, Putnam; Karen Routledge (2018), Do You See Ice?: Inuit and Americans at Home and Away, University of Chicago Press.

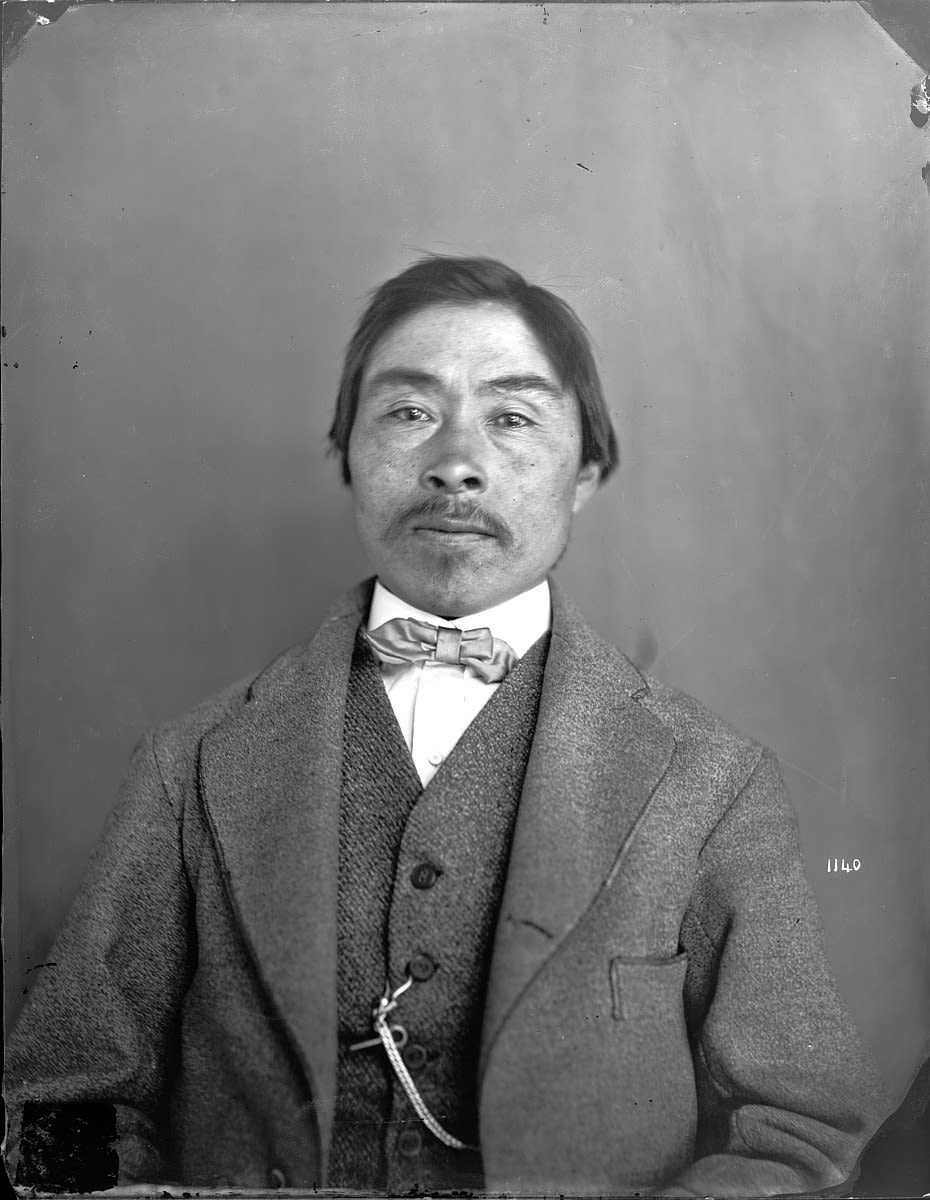

Portrait of Ipiirvik. Held at Smithsonian Institution Archives

Portrait of Ipiirvik. Held at Smithsonian Institution Archives

Portrait of Tookoolito. Held at Smithsonian Institution Archives

Portrait of Tookoolito. Held at Smithsonian Institution Archives