Rachel Meller

Darwin alumna

Dr Rachel Meller

knew little about

her mother’s family,

until a box of papers

revealed an

untold story

and led to her

literary debut

Rachel Meller’s story begins with a shocking loss. Three months after her birth in 1953 her mother, Ilse, took her own life. Rachel grew up knowing little to nothing about Ilse, with her only surviving maternal relations, her grandmother and aunt, on the other side of the world in San Francisco.

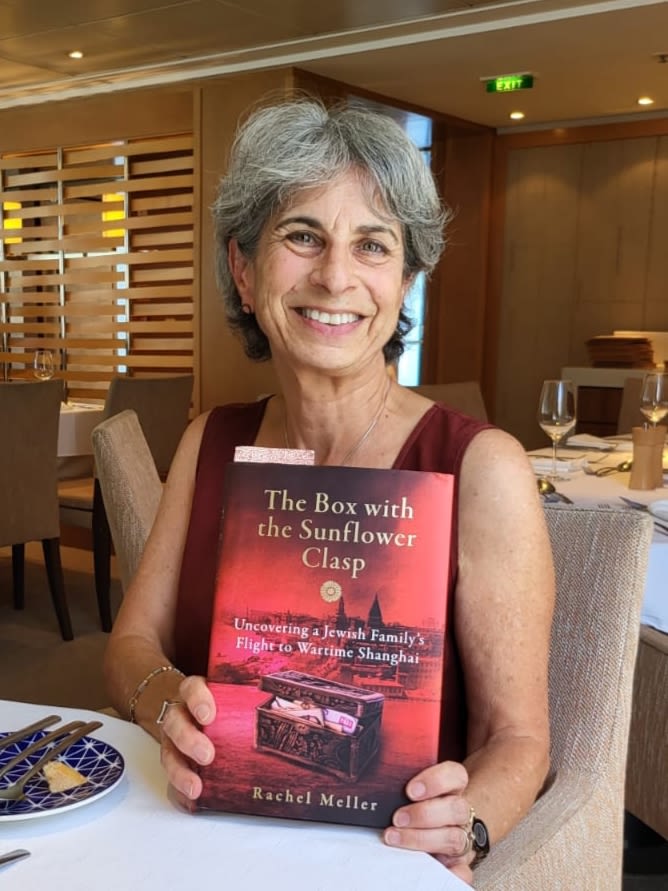

But a box of papers, concealed in a cabinet left to her by her aunt in the 1990s, provided some answers which Rachel has taken the past six years to piece together. In a moving and compelling new book, she brings to vivid life the relatives she barely knew, and illuminates a little recognised aspect of history, by following her aunt’s experience as a Jewish refugee from 1930s Vienna to Shanghai.

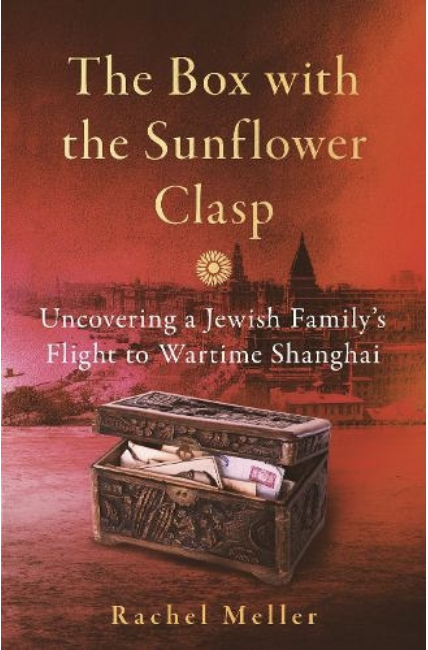

Rachel completed a PhD on hormones and behaviour at Darwin in the mid- 1970s, before pursuing a career in communication and training. The Box with the Sunflower Clasp, her first book, was published in 2023. She talked to Laura Kenworthy about the poignancy of getting to know her family decades after their deaths, and the thrill of making her publishing debut at 69.

At what point did you discover the treasure trove of letters, photos and documents that your aunt Lisbeth had left you?

I knew that she had left me the cabinet after her death in 1996, but this thing inside wrapped in paper was a surprise. I looked at it immediately, but then I just put it to one side. And do you know, genuinely, when you’ve had something in the house for a long time it becomes invisible. I literally did nothing with it, until my brother-in-law gave me a book of interviews with Jewish wartime refugees to Shanghai, which included an interview with Lisbeth. That was in about 2012. I’d always wanted to write a book, and with the combination of these sources and the University Library, I thought “I can do this.” The seminal textbook on the period is at the UL and I literally owned it for about three years, I kept renewing it and renewing it.

When did it become clear that the focus was going to be your aunt, rather than your mother, who had an equally fascinating story coming to London on her own?

Well, the box was all about my aunt.

The motivating force was I thought if I learn more about my aunt, and where she grew up, and the family history, maybe I’ll find out more about the sisters and my mother. But also, I asked loads of people if they had heard about the Jews in Shanghai and virtually nobody I asked, who lived in the UK, knew about this story. So that motivated me to keep going, finding out more about my family but also thinking will people say “Really?! 20,000 Jews went to Shanghai? Why did they go to Shanghai?”

So did you grow up knowing anything about your mother and your family? Did your father try to make sure that they were part of your life?

No, not at all, the opposite. Ilse’s name was virtually never mentioned. If I tried to ask my elder sister she tightened up, which is understandable because she was six when our mother died. In a way I was the lucky one because I didn’t know what I was losing. So I could be more dispassionate trying to piece the story together.

But I didn’t want to upset my dad, because he’d had a heart attack in his 40s and I didn’t want him to get stressed by me raising these subjects again. And my stepmother, Ruth, would never have met Ilse – they must have talked about her but it was sort of taboo. I tried to ask my aunt what Ilse was like but as far as I remember I got nowhere. So I had to learn some things from reading history.

But you’d had some sort of long- distance relationship with your aunt?

Yes, I think from when she first started coming to England, maybe the late 1960s, early 1970s? I think it just became more common to fly. But she never went back to Europe to see her sister. I kind of hadn’t appreciated it – it was only writing the book that made me realise, wow, she never saw her sister again after 1938.

Did they write to each other?

They did write to each other. Just recently, before my own sister died last year, she said “oh, you’d better have this,” and there was this big plastic box. My nephew went through it about two or three weeks ago and found letters my grandparents had written to my mum from Shanghai. So they must have communicated, I now know that they did. But I had no evidence of that before so I had had to imagine that they knew what was going on.

It’s an amazing gift to be able to bring them back to life and honour their experiences in this way. You’re very honest about the fact that in real life you found Lisbeth hard to warm to. I’m impressed, given that, by your commitment to understanding and presenting her perspective.

When I started the book, everyone said ‘why would we read a book about someone you obviously don’t like?’ I had to tone it down! But I wanted to find out her story, and it’s been cathartic – I think I’ve developed more sympathy for her. I always had sympathy for my mother because I know having worked on hormones and behaviour that you’re at the mercy of these bloody chemicals. Mental illness is awful.

Yes, so your PhD was on hormones and behaviour – did you study medicine first?

I tried to study medicine – I wanted to be a psychiatrist – but the all-girls school I went to said ‘oh, it’s far too risky, you can’t apply to six medical schools because if you get rejected by all of them you’ll have nothing.’ And actually that was completely the wrong advice, because all the medical schools saw that I’d applied to Sussex to do neurobiology, and they thought I wasn’t serious about medicine. So I didn’t get anywhere with medical school. But to be quite honest it was a huge relief because I’m so bad at dissections and practicals, and I’m squeamish and I panic and it wouldn’t have been a natural fit!

So you went to Sussex, and then came to Darwin straight afterwards?

Yes. I enjoyed doing my research project at Sussex in the third year, and then I saw this PhD at Cambridge advertised in the paper, on hormones and behaviour, so I thought well I’ll be brave and apply.

After Darwin I was lucky enough to get a Mental Health Foundation Junior Research Fellowship to carry on. But the work I was doing became more and more practical, and I just don’t find lab work interesting, however wonderful the question. And then I got married to the head of the lab. He wasn’t my supervisor, but it felt wrong to stay. So I went to work on child behaviour at Madingley (Zoology’s sub-department of Animal Behaviour), but after I had my first child in January 1982 I wasn’t allowed to come back part-time.

So I got a job at Cambridge University Press subediting science books, which was fantastic, but I really wanted to be writing. I eventually got this very good job in a place with a totally flat hierarchy, which was originally called Information Transfer and is now called Acteon Communication and Learning. And I stayed for 29 years. So that’s my career history – and this is my second career!

The Box With The Sunflower Clasp: Uncovering a Jewish Family’s Flight to Wartime Shanghai is published in hardback by Icon Books, and will be available in paperback from April. Rachel is currently researching her next book, an exploration of research into consciousness and the possibility of its persistence after death.