Darwin Heritage

The Darwin Family and Cambridge:

Preliminary Research Scoping

In 1963, Newnham Grange and the Old Granary, home of a branch of the Darwin family since 1885, became available for the first time in almost 80 years. These buildings became the nucleus for the first graduate college in the University of Cambridge and, Darwin College was subsequently named in their honour. Elements of the Darwin family’s crest, such as the three escallops, were incorporated into the College’s crest in 1966, emblems used by the family since the eighteenth century that continue to associate the college with one of the University’s most famous dynasties.

A new research project, headed up by Edwin Rose hopes to provide an overview of the scientific, literary, and artistic work of the Darwin family and their relationship with Cambridge from the time of the eighteenth-century polymath Erasmus Darwin to the early 1960s.

This research aims to decentre the activities of the well-known naturalist Charles Robert Darwin (1809–1882) to understand more about the work of his forbears and descendants.

One of these, his son, George Howard Darwin (1845–1912), Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy, purchased Newnham Grange in 1885.

Since its foundation Darwin College has been the custodian of many Darwin family portraits and artifacts, starting with the portrait of Erasmus Darwin by Joseph Wright of Derby painted around 1770, an image renowned as a masterpiece of enlightenment portraiture.

More than fifty years before his famous grandson, Erasmus published controversial evolutionary theories, campaigned for the abolition of slavery, supported the French Revolution, promoted education for women and challenged orthodox Christian views. Erasmus took a BA at St John’s College (1754)

In 1791 Erasmus described his time in Cambridge to John Horsman:

‘At Cambridge I never spent evenings with drunkards, but drank tea with company either at home or abroad every day, and became more acquainted with all that I thought ingenious, or that I could learn anything from.’

Cambridge presented members of the Darwin family with the perfect intellectual setting for innovation. Although Erasmus’s son Robert (a physician in Shrewsbury), had little to do with Cambridge, Robert encouraged his sons to study at Cambridge which set Charles on the path that would define his life’s work.

After his time at Cambridge Charles relied on a network of collaborators to obtain information and by the 1870s Charles’s children were key figures. His daughter, Henrietta Darwin (later Litchfield) was responsible for editing the text of The Descent of Man (1871) and the College owns a copy of the first edition, inscribed by Charles himself. This book was presented to Laura Mary Forster (1839–1924), a family friend and aunt of E. M. Forster, who maintained a lifelong correspondence with Henrietta.

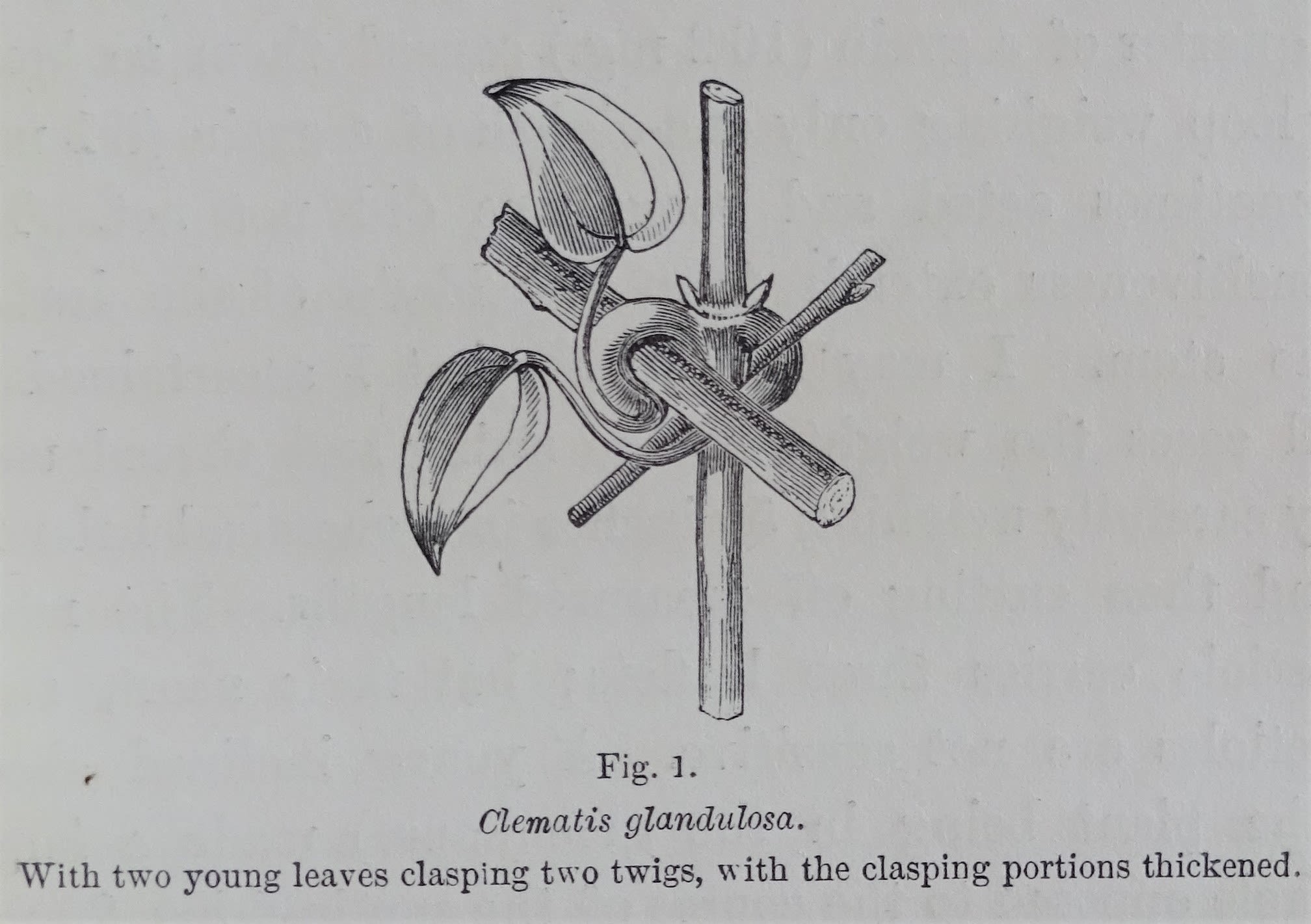

Another example of these collaborative working practices can be seen in Darwin College’s copy of The Movements and Habits of Climbing Plants (1875), the illustrations in which were produced by Darwin’s second son, George Howard Darwin (1845–1912).

George Darwin continued to collaborate with others when researching the natural world for the rest of his life. By the time he purchased Newnham Grange, George was engaged in a global correspondence network, sourcing information on the relationship between tides and lunar motion while founding the field of geophysics. Research on George Darwin’s archival and book collection, now held by Cambridge University Library and the Whipple Library, has uncovered details of correspondents in the USA, South Africa, Australia, Greenland, and several Indian cities.

George Darwin’s network was further augmented through his presidency of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). His networking relied on the British Empire, an involvement with imperial projects that this research will investigate, to show how this shaped scientific research but also with an intention to unlock the activities and contributions of numerous hitherto unnamed collaborators in the production of natural knowledge.

George’s wife, the American socialite Maud du Puy, and their children, often participated in these trips. Gwen Darwin (later Raverat) accompanied her father when he travelled to Boston to give the Lowell Lectures in 1897—the basis for his book The Tides and Kindred Phenomena in the Solar System (1898).

Gwen is best known as one of the first artists to develop woodcut engravings as an artform, many of which illustrate her memoir Period Piece: A Cambridge Childhood (1952). Gwen’s woodcuts, such as that of Ely Cathedral, became well known across the country as the main images used by London North Eastern Railways in their advertising campaigns. Working in collaboration with her brother-in-law, Geoffrey Keynes, Gwen produced the designs for Job: A Masque for Dancing (1931). The music was composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams, (Ralph’s two great-great-grandfathers were Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95), the founder of the pottery at Stoke-on-Trent, and Erasmus Darwin).

Sir Charles Galton Darwin (1887–1962), the last Darwin of Newnham Grange, worked for the National Physical Laboratory, making several breakthroughs in the fields of statistical mechanics, quantum physics and working with scientists such as Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr.

Overall, this ongoing research project, aims to uncover the Darwin family’s contributions to the arts, sciences, and literature, creating a new understanding of the rich intellectual heritage an association with the Darwin family brings to the College. The intended output of this work is an exhibition designed to display objects from the College’s and other Cambridge collections to illuminate the activities of a family that shaped the arts and sciences since the mid-eighteenth century—in a space that continues to inspire research and innovation.

Darwin College Crest

Darwin College Crest

Erasmus Darwin Portrait

Erasmus Darwin Portrait

The Descent of Man (1871) first edition inscribed by Charles Darwin

The Descent of Man (1871) first edition inscribed by Charles Darwin

George Howard Darwin’s illustration of Clematis glandulosa on page 47 in Charles Darwin’s The Movements of Climbing Plants (1875).

George Howard Darwin’s illustration of Clematis glandulosa on page 47 in Charles Darwin’s The Movements of Climbing Plants (1875).