Darwin and Sustainability

Sustainability and Public Health

Professor Carol Brayne

Professor Carol Brayne

Carol Brayne CBE is a Fellow of Darwin College, a Professor of Public Health Medicine and Co-Chair of the Cambridge Public Health Interdisciplinary Centre at the University of Cambridge. She is a medically qualified epidemiologist and public health academic. Her main research has been on longitudinal studies of older people following changes over time with a public health perspective and focus on the brain. Jonathan Goodman is a PhD student in anthropology at Darwin interested in evolution, behaviour, and health, and is digital editor at Cambridge Public Health. He is also a science writer and former public health researcher at Imperial College London. Here they discuss Sustainability and Public Health.

The view that sustainability and public health are inextricably linked is not new. For more than half a century and indeed since time immemorial, people have been aware that living well and keeping our planet healthy are not separate issues. But this has not been the predominant societal concern, and instead we have focused on particular types of economics and production. There appears to be a lack of recognition that aligning sustainable approaches to public health is vital for healthy life-courses and the lives of those coming after us. To understand the myriad relationships between the health of our planet and the health of our societies, it is necessary to think about how prevention is related to health. In public health, prevention is about more than drains, vaccination, screening, and individual behavioural adjustments. If someone lives in a violent home, on a smoky street, or with inconsistent access to clean water – each of these, as with innumerable other factors, determines the health risks we face across our life-courses, both individually and in groups. Our second line of prevention deals with the detection of early indicators or risk for later illness: this is ‘early detection’ or screening (such as for HPV in the prevention of cervical cancer). And tertiary prevention - our last line of defence - is to mitigate against the impact of extant diseases after they are identified and enable appropriate support towards the end of life. All these together, including working at the collective level, are aimed at enabling lives to be as good as they can be. All three approaches are therefore essential for the functioning of a good health system, both at international, national, and local levels. Unfortunately, of these approaches, primary prevention is perhaps the least understood and the roles each play in overall health of the population even less so. The perception can be that public health is all about multiple screening and early detection activities, personalised lifestyle guidance, and a lot of medical intervention, but the best systems are actually those that most effectively reduce our individual exposure to risks.

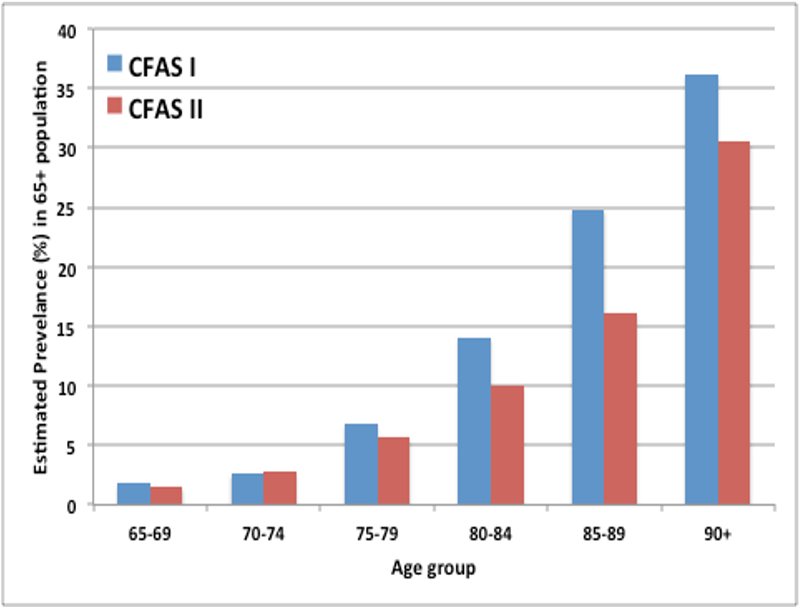

Above: Estimated Prevelence of Dementia in 65 Plus Population in 1990 (blue) and 2010 (red)

Above: Estimated Prevelence of Dementia in 65 Plus Population in 1990 (blue) and 2010 (red)

Health, although it might seem so, is not primarily our own personal decision. Health and wellbeing comprise many things, from how we are constituted, to our life course and even the many types of environment in which we exist; the psychological, the social, the physical, the emotional and the cultural. There are many, many influences on our health throughout our lifetime, and all of these have their own impact and potential for improving - or not improving - the sustainability of our societies and, by consequence, our species.

Take, for example, dementia. In our own work to establish how common dementia is in the population, we studied older people in varying geographical localities. We first did this around 1990 and again in 2010, using the same methods in the same places. We found significant differences in the proportion of people with a diagnosis of dementia between the two generations. In both studies there was the expected dramatic rise in dementia prevalence with age, doubling every five years after 65. There was also something rather unexpected, a more than 20% decrease age for age in the more recent generation. This suggests that, in the intervening 20 years, there was a drop in dementia prevalence across generations: but, given a lack of improvements in care and screening, why was this case? A public health perspective, focusing on primary prevention, helps to answer this question. We know that social structure may have a profound influence on neurological events. And while some physical metrics - such as improvements in heart disease and stroke rates - may well be associated with these changes in dementia prevalence, there have also been improvements in maternal and early life health, education, vaccination programmes, nutrition, and social welfare systems. The introduction of the NHS underpinned some of these aspects, but by no means all.

Of course, all these are changes to types of environment and are likely to all contribute to a greater or lesser extent to changes in the prevalence of brain disorders and mental health or wellbeing. What the public health perspective offers is the sense of malleability of our health: we are organisms that live across generations and between groupings within our societies. Everything about those societies, and the subgroups within them, contribute to our own health. Focusing on the factors linked with dementia elucidates this link further. Among these are poor education, hypertension, diabetes, depression, obesity, infrequent social contact, and air pollution. Each of these is, in turn, linked with systemic problems in our societies – locally and globally, which contribute, over time, to the physical and social environments that lead to a greater dementia risk in some populations.

Earth Day Poster from 1970

Earth Day Poster from 1970

We cannot address any of these problems without addressing all of them. Inequality, health risks, and environmental issues are inextricably linked, and to prevent people from developing issues like dementia, we need, as a society, to focus on addressing the sources of these problems. While the improvements we have made, both social and medical, have helped to reduce dementia risk among the elderly, they have also allowed inequality to persist and sometimes worsen – contributing to poor air quality and poor lifestyles among those without means. To reduce dementia risk in the future, addressing inequalities and the environment, as well as exemplifying healthy populations and healthy communities, seems likely to yield healthy brain ageing, and healthy ageing more generally. Some countries with a primary prevention-focused health system demonstrate that good health outcomes are possible without enormous expenditure. So perhaps, instead of focusing only on the novel, expensive screening tools and treatments used in the second and third lines of defence, we should learn to rely more heavily on the f irst, preventive line, and in academe shift our emphasis to invest more in these areas of evidence generation to inform the best possible policies. This will improve public health and reduce healthcare spending, and consequently, will help to improve the health of our planet. We are at a critical moment where we can align the agendas of health and sustainability. Communicating the links between these agendas, both to the healthcare world and the public, is essential for the success of each.